Archive Record

Images

Additional Images [8]

Metadata

Catalog number |

1997.2.2616 |

Object Name |

Newsletter |

Date |

1996 |

Description |

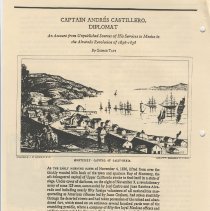

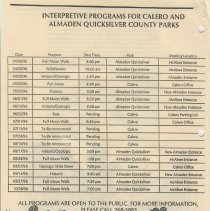

TITLE: Quicksilver County Park News SUBTITLE: Newsletter of the New Almaden Quicksilver County Park Association Issue # 44 Spring 1996 Newslettcr of the New Almadcn Quicksilvcr County Park Association SPRING 1996 ISSUE 44 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE This Spring edition is brought to you with great expectations that the grounds around the Hacienda Furnace yard will be prepared for the construction of the Mine Office for the Museum. The bids have gone out for the protection of the creek from the calcines and work is supposed to begin the first of May 1996. We are very anxious after 16 years to see this project started. The Museum has received many donations in the past months and we need help arranging them. If you have some time , please call Kitty to offer assistance. Two large paintings of New Almaden and the Mines are in need of placement. Suggestions as to their proper location in the Museum will be helpful. Your Association received the Most Outstanding Group award at the Volunteer recognition ceremony held by the Santa Clara County Parks Dept. at Sanborn Park in April. Congratulations to all the members for your work, interest and donations that make this Association so special. A beautiful plaque is in a prominent place at the Museum. Come see. Trail Day , Apri127, 1996 was a terrific success. We had 50 people on the extension of the Great Eastern Trail (a hackin' and a hewin' ) and completed the trail so it is now open. Your Association fed all the volunteers in Englishtown and some other volunteers who were working on the other side of the Park on the New Almaden Trail. The day was great, and we made headway into the direction we would like to go with the trails plan for the park. If you know something about the area between the April Workings and the Great Eastern Tunnel, we need some help on the naming of the new trail. We have two suggestions, Mary Hallock Foote Trail or(M.H.FooteTrail) or Bush Tunnel Trail. Mary Hallock Foote lived right above the connecting spot of the new trail and the April Trail and we imagine her walking this road. On Edgar Bailey's map, the Bush Tunnel is between the Great Eastern and the April and March Tunnels.Please call me if you have some ideas. The Spring wildflowers are magnificent both at McAbee and Hacienda . Also all along the New Almaden Trail, the Chinese houses, the buttercups and the poppies are splendid. Have some fun hikes. Kitty Monahan (268-6541) NEW ALMADEN MINING REVIEW GUADALUPE MINE During the 1860's the price of mercury climbed to $63.13 per flask but the retail price to the miner was much higher. This high price had one beneficial result it led to a sudden burst of interest in prospecting for and developing additional quicksilver mines. During the years in which the New Almaden was closed due to a federal injunction, operations were begun at three mines in the area not far from New Almaden itself: the New Idria, Guadalupe, and `Enriquita. At almost the same time several mercury mines were located north of San Francisco Bay, in the hilly region embraced by parts of Napa, Lake and Sonoma counties. Ed note Last December the following article was submitted by David W Knapp, Sr, grandson of Thomas Tonkin and author of Cousin Jack a book about Thomas Tonkin s life. as a member who enjoys your articles very much, 1 enclose a synopsis of a chapter in my book, Cousin Jack. which tells of the bravery of my grandfather, Thomas Tonkin. on February 24, 1885, while he was the chief engineer on the Randol Shaft. \When Thomas Tonkin died in San Jose on December 22, 1942, the Mercury ran both his photo and a lone article entitled Hero of the Mines." THOMAS TONKIN. THE HERO OF THE MINES So he was proclaimed on the afternoon ceremony held in English Town when James B. Randol, then superintendent of the mines, presented Thomas Tonkin with a solid gold watch which was inscribed "TO THOMAS TONKIN FROM THE QUICKSILVER MINING COMPANY IN RECOGNITION OF HIS GALLANT CONDUCT AS AN ENGINEER-FEBRUARY 24, 1885." Thomas Tonkin proudly wore and displayed it every day until his death in 1942. Thomas Tonkin, born in 1856 in St. Just, Cornwall, followed his father and two elder brothers to the Almaden Mines at the age of 18 years and was subsequently joined by his mother and younger brother. He lost his right hand in an explosion three years later. What event could possibly bring the entire mining community to a stand-still and warrant the prominent superintendent to proclaim to the assembled mine bosses, miners, their wives and children the bravery of this twenty-nine year old man who was still weak from his ordeal? It was to celebrate Thomas Tonkin's brave act of courage that took place just three months before and of which each of them was well aware from the day of its occurrence. On that day Tonkin had arrived earlier than usual at the shaft house in the morning. He wanted to make certain that the engineer on the opposite shift had finished his required chores and had "trimmed" the boilers. Tonkin had suspected, and evidently rightfully so, that the engineer had been "HERO OF THE MINES a little lax in his duties as lie had had to complain to the engineer on several occasions- about the way the steam engine and the boilers had been left for his shift. Tonkin, now the chief engineer and also in charge of the other engineers working on the Randol Shaft, took his position of authority very seriously. The new shift started to arrive, and the miners congregated topside waiting to board the three skips (cages) that would take them down into the mine. When sufficient men had gathered and the morning shift whistle had blown, Tonkin took over and pressurized the huge steam engine that turned the twenty-four-foot diameter fly wheel which suspended the gigantic cable attached to the cages. The descent into the shaft was controlled by a large steel brake lever that allowed steam pressure to close a drum, which in turn slowed or completely stopped the cages in their descent. The speed of descent was also controlled by this lever, and if the lever was completely pushed forward the cages would free fall to the rock bottom of the deep shaft. As the whistle blew its warning that the day shift would commence, the first of the miners got into the bottom of the three cages and Tonkin lowered the entire lift to the next cage level where another group of miners boarded. Finally, when the uppermost cage was filled, Tom released the brake slightly and the men disappeared into the depths of the shaft with the cable whining in a controlled fall. The various levels of the shaft were marked on the huge cable drum that slowly revolved as the cable extended or contracted. From these marks Tonkin could determine what level to stop to lift to discharge the miners. Today all the shifts were going to the very bottom level. which was more than eighteen hundred feet below the surface. The cable would spin out as the skip's weight pulled it faster and faster. Tonkin carefully watched the drum so that. several hundred feet short of the lift's goal. he could slowly brake it to control its descent and be able to stop the cages short of the rock bottom. After the load was discharged, another group of miners, up to eighteen maximum, would get on the cages to be returned to the surface. In this manner one shift would descend and the other, the finishing shift, would come to the top. Having so many men's lives depending upon his one good, sturdy hand make Tonkin proud. He had never, to this date, had an accident, and the men trusted his judgment and strength implicitly. He had felt, at first, that they might be a little edgy to think that a one-handed engineer held their lives by a thread. Sensing this, Tonkin would go to extra lengths to show them the tremendous strength he had now built up in his one good arm and hand. In order to work the lift and to adjust the dials and valves of the steam engine and the boilers, it was necessary to have the engineer sit in a chair similar to the engineer on a steam locomotive. The heat of the large furnace poured forth onto his back, and the roar of the fire consuming the wood or coal was deafening, requiring one to shout when this particular operation was in progress. The dozens of miners on a shift would wait until the cage reached its level, and then Tonkin, not knowing or having any signaling device, would wait a reasonable time to allow the miners below to disembark the cage. He would then, out of an abundance of caution, jiggle the brake handle, thereby causing the cage to bounce up and down several inches. This acted as a warning to those far below that he was about to pull the lift upwards or to move it to another level. "When that there cage jerks, m' lovies. 'ee better be getting 'ee arsh out or 'ee be mince meat.' an old miner would instruct the novices, as more than one miner had fallen to his death when he attempted to board a cage too late. This day was like any other. Several lift loads of miners had been dropped to the bottom, and about half of the shift was now underground. The lift had just been reloaded and had plunged into the dark hole of the shaft. Tonkin was watching the drum to see how far they had descended when an odd, unusual hissing sound emitted from behind him. As he turned to see what the strange sound was, there was an earth-shaking, thunderous explosion. One of the huge boilers had exploded in a deafening sound. It sent volumes of hot steam into the shaft house, completely engulfing Tonkin as he sat holding the brake level that controlled the lift on its long descent to the bottom of the shaft. Tonkin was blinded by the blast of this hot air and water, and he groped to hold onto the brake. The pain was beyond endurance, he thought, yet he held on, fully aware of what would happen if he released that steaming-hot brake handle. The miners who were still in the shaft house awaiting the descent ran screaming out of doors as the burning hot air commenced to scald them. Tonkin, now realizing what had happened, set his teeth so tightly that the pain from his jaw helped him overcome the more intense pain of the scalding he was still taking from the constantly emitting steam. He also set his mind and determination that no matter what, he would not release the brake and send those twelve souls over one thousand feet to their instant death. He was literally being cooked alive, and he would openly moan and then scream aloud with the intense torment; however, he refused to unfasten that firm left-handed grip on the brake. His eyes, now bleary with pain and dimmed from the hot, blasting steam that never ceased pouring over him,were fixed on the drum that would indicate when the next level would be reached. He silently prayed to God for just a little more strength and consciousness, as he felt weak and faint. He must hold out! It was the greatest test and feat that he would ever be called upon to perform, and he most ...he must do it! He could see the marker slowly, oh, so very slowly, he thought, descending to the next level. He knew that when it did, he must have enough strength to slowly bring the brake handle back and slow the cages to stop them, one by one, and to disembark the three tiers at that level. The pain became more intense. He could feel his facial skin searing and turning leathery. He could see his hand being cooked red by the steam and its inner palm blistered by the iron handle on the brake. He wanted to let go and dash for the cool air outside; however. he thought of his friends on the lift. If he failed them, theN would all surely die. Would English Town say it wouldn't have happened if the engineer had had two good hands? The miners, looking back through the shaft door, stood awestruck in amazement to see the fortitude and courage of this man who would sacrifice his life for his fellow workers. Watching him in his agony and now being assured that he would not leave his post, some encouraged him to hold on while others yelled for him to get out. Some of his close friends wept. Hearing their encouragement gave Tonkin the extra strength he needed, and his bleary eyes now saw the lift was nearing the eight hundred foot level. Calling upon all his energy, he pulled the brake back and stopped the cages. He immediately started to jerk the brake to warn the miners something was wrong and to get off quickly. He waited until what seemed like eternity, and then all became dark. He had mercifully passed out, and the empty cages plunged to the bottom of the deep shaft and smashed to bits. All twelve of the miners had gotten off-none were lost. As the steam slowly decreased, the topside miners, now covered with dampened burlap sacks, hurried to the stricken engineer and carried his limp form, horribly burned and scalded, out into the open air. "I be one who be saying to 'ee, m'lads, ee will never be seeing an act of bravery like that again in ee `ole lives. Me 'at 's off to Tom Tonkin! Now effen the good Lord will only spare `is soul," said the mine boss, who had not descended as yet that morning. Tom w as carried to an open wagon and placed under a blanket. He was still unconscious and would be taken to the new medical clinic that had just recently been established on tire hill. There he would be treated by a physician who was, fortunately, in attendance that day. He would wear the scars of the steam on his face and hand the rest of his life. proud tokens of a heroic act. The gold watch is now proudly owned by one of Thomas Tonkin's great-grandsons, who is appropriately named Thomas Tonkin. CAPTAIN ANDRES CASTILLERO, DIPLOMAT An Account from Unpublished Sources o f His Services to Mexico in the Alvarado Revolution of 1836-1838 By GEORGE TAYs MONTEREY- CAPITOL OP CALIFORNIA. As The EarLY MORNING MISTS of November 4, 1836, lifted from over the thickly wooded hills back of the town and spacious Bay of Monterey, the oft-beleaguered capital of Upper California awoke to find itself to a state of siege Under cover of darkness, on the night of November 3, a revolutionary army of some 125 men, commanded by JosE Castro and Juan Bautista Alvarado and including nearly fifty foreign volunteers of all nationalities masquerading as American riflemen led by Isaac Graham, had stolen stealthily througn the deserted streets and had taken possession of the ruined and abandoned fort, which stood on in eminence several hundred yards west of the crumbling presidio, where a company of fifty-five loyal Mexican officers and soldiers commanded by Governor Gutierrez were quartered During the day and night of the 4th and early morning of the 5th, negotiations for the surrender. of the post were carried on between Castro and Gutierrez. In the meantime, half of the latter's soldiers deserted him and the rebels were materially aided with arms, ammunition, and other supplies, by some eight or ten foreign vessels, specially those owned by Captain William S. Hinckley,which by some strange Coincidence had assembled in Monterey Bay at that particular time. The rebels had also raised the moral support of Commodore Edmund B. Kennedy, Commander-In-chief of the Asiatic squadron of the United States, who had visited Monterey to make some absurd demands upon the authorities and who had sailed south only four days before, after receiving information about the intended revolution. The negotiations completed, Governor Gutierrez capitulated at 8 A.M. on November 5. having received full assurances for the safety of the lives and property of himself, his officers and his men. The revolutionists then took formal possession of the capital and on the 7th proclaimed California a free and sovereign state, independent from Mexico, until such time as the federal system of 1824, which earlier in the year had been supplanted by centralism, should be restored. This was done amidst great festivities of rejoicing and resounding vivas! to the federation, to liberty, and to the free and sovereign State of Alta California. The Californians gave many reasons for the uprising, the chief one being the abolition of the federal system in Mexico and their refusal to endure the subsequent despotism. More potent reasons, however, were the ambitions of the young Californians to hold important officers in the territorial government the desires of the principal Californian families to acquire the rich mission properties; the hatred of the Californians for things Mexican; and finally the quiet instigation by the growing foreign element, especially the Americans, who were anxious to see and help the Californians revolt so that this rich territory might be turned into another Texas: Early in 1837, the Mexican Government decided to take some action, and a bill was passed in congress providing that a loan of 60,000 pesos be secured from the Pious Fund, with which to finance the proposed military expedi- tion. This turned out to be a dream, for by then the Pious Fund was practically exhausted. Nevertheless, for the succeeding four months, plans for the expedition went forward although the loan was not forthcoming. On June 6, - 1837, a naval officer, Captain Lucas F. Manso, submitted a complete estimate of the cost of the expedition. It was to consist of six hundred fully equipped men under a competent commander, General Iniestra, and was to go by water in four transports convoyed by two war vessels, with provisions for a three months' campaign. The total cost of the expedition was estimated at 59,335 pesos. In the meantime, an important event took place in Mexico which was to influence greatly the course of California politics for the following two years. At that time the government was in desperate circumstances, being unable to raise the money with which to send the military expedition to California. Already, it had consented to send Castillero in an effort to bring peace to the territory. And it continued to grasp at straws, however weak, which might aid it in that undertaking. One of these broken reeds which it clutched was Don Carlos Antonio Carrillo who up to that time was helping Alvarado in Santa Barbara. Early in the year. Don JosE A. Carrillo, who was in Mexico, began to whisper into the government's ear that if his brother was appointed governor of California the revolution would end At first. little heed was paid to him but as other plans failed the suggestion was finally acted upon, and on June 6, 1837, the President appointed Don Carlos as governor.' Meanwhile, Captain Portilla, with Captain Zamorano acting a secretary, set out for Los Angeles with his army of seventy Californians and a few trappers from New Mexico on June 13. While preparing to depart, on the 12th, Portilla received a message from Fr. Felix Caballero of the frontier Mission, enclosing a copy of the new constitution of 1836, also announcing the arrival of Captain Andre Castillero as commander of the frontier company. When Portilla received the letter, he assembled his army and the citizens of San Diego and had them take an oath to the new constitution. The following day he wrote to Captain Castillero requesting the aid of the latter 's troops if possible He then marched his army to Mission San Luis Rey, where he stayed June 14 and 15 to repair some equipment At that place Captain -Castillero overtook the army on the 15th, with a sergeant and eight dragoons. - Upon receiving Portilla request for aid. Captain Castillero at once decided to act under that clause in his commission that empowered him to act as he saw fit, according to the circumstances. At San Luis Rey he informed Captain Portilla, orally, that he had been commissioned by the Mexican Government to settle the revolution; but that because of the haste with which he had set out from the frontier, he had left his credentials behind with his luggage. Due to that incident and to the fact that he had been a fellow-officer under Gutierrez only a few months before, Portilla and his officers believed him. Henceforth, they recognized him as invested with the character of an envoy from the national government for the stated purpose, and agreed that he might discharge his commission within sight of their army: By his actions in this case, Castilero showed himself to be a shrewd diplomat. In fact, his commission was only a left handed .affair issued to him by Don josE Caballero with the approval of the national government, but it could hardly be construed as an actual grant from the central authorities. Furthermore, it was so vaguely worded that he would have found it difficult to establish his position as an envoy. He probably reasoned that if he showed the document to Portilla, he might not accept it, as he very likely would not have done. He also may have thought that if he made verbal claims, leaving the proof behind, there was a chance that the other officen might believe him, sin" they had known him as a comrade for several years, and none of them could be sure that he had not been to Mexico with Gutierrez and really been appointed as an envoy. His scheme worked and he did not have to present his credentials, thus saving himself much embarrassment. Nevertheless, before he had finished his work, Portilla, Argilello, Bandini, and others began to suspect that his claims were spurious. On December 5, 1837, the Naval commandant of San Blass Don Francisco Anaya, had Santiago Aguilar make a formal disposition under oath about conditions in California. This was forwarded to the Minister of War, and received on December 13. Aguilar aerated all that he has said in his report from Mazatlan, but laid special stress upon the activities of the Americans, and upon Castillero's part in keeping Alvarado in power. He said that Castillero had promised in the name of the government, that it would not interfere with the Californians in anything; that all the principal officials would be native Californians and that Mexicans would no longer rule them. With all those adverse reports of criticism reaching the government, soon after he arrived in Mexico, Castillero found it increasingly difficult to convince the administration that Alvarado should be given a permanent appoint-ment as governor of California. It is impossible to say what methods he used in arguing his case, as most of the negotiations were conducted orally and only occasionally did he put anything in writing. On one of these rare occasions. December 19, 1837, he wrote a brief letter to the War Department stating reasons why some of the Mexicans in California had been imprisoned. Evidently, after receiving Aguilar's sworn statement the Minister of War called Castillero to answer the accusations made against him. Castillero wasted little time in answering his accusers, because he only had to show that they were engaged in criminal activities. However, he had greater difficulties to overcome in helping Alvarado, because on arriving in Mexico, he found that as early as the month of June the government had appointed Don Carlos Carrillo as governor of California. Not only did that appointment make it extremely difficult for Castillero to get Alvarado accepted as governor, since Carrillo's appointment first had to be revoked, but also, all of Castillero's work in pacifying California had practically been undone. By January, I838,the issues had been drawn and the peace of California was again broken. All of Castillero's work of the previous year was now undone, through the ignorance of the government, the ambitions of the Carrillos and no fault of his own. We need not go into the details of the 1838 campaigns here; other histories have done that Suffice it to say that early in January Carrillo sent a request to Mexico for two hundred armed men. By February, California was again engaged in civil war and the armies of both factions were marching and counter-marching over southern California. In all the campaigns, the Alvarado army had the decided advantage of more active,able and resolute leadership; so that by midsummer of 1838 Carrillo's army had been crushed and the pretender as well as most of his followers were safely in prison either in Santa Barbara or Sonoma. Meanwhile, Castillero had been laboring in Mexico. He had conferences with cabinet ministers and the president, trying to bring about a definite solution to California's troubles by advising the rejection of Carrillo and the appointment of Alvarado in his places However, due to the general apathy of the Mexican Government toward all things Californian and to the perpetual unrest that troubled Mexico, Castillero encountered almost insurmountable obstacles to his plan. It was not until the reports of the new civil war in California began to arrive in Mexico, in 1838, that the administration began to pay heed to the situation. By that time. also, trouble with France was in the air and it behooved Mexico to have California at peace or it would have some foreign power fishing in those troubled northwestern waters. Thus, when the news of Alvarado's success in crushing Carrillo in April, 1838, arrived in June, the government began to act. On August 13, the Catalina arrived at Monterey with a letter from Castillero to Alvarado, saying that he had finally succeeded and that he was about to start for California as a commissioner from the government. On receipt of that letter. Alvarado gave up all idea of surrendering his office until Castillero's arrival. There was nothing to do but await the California's arrival with Castillero aboard, but due to the war with France, his departure was delayed from July until September and it was not until November 15, that the California anchored at Santa Barbara On landing, Don Andres sent word to Alvarado and Vallejo that he had brought documents that would establish them in their offices, and requested them to come south for a personal conference. The most important of the documents brought by Castillero were: a decree of June 30, 1838, creating the Department of California; a commission as captain of the San Francisco Company for Vallejo; a vote of thanks to the Department for the gift of the California to the nation; a decree of amnesty for all political acts and opinions during the past troubles; with an order to Carrillo stating that Alvarado should act as temporary governor; an appointment for Vallejo as General Commandant; and finally, personal letters to both Alvarado and Vallejo from President Bustamante, who expressed his high esteem for them and confidence in their patriotism and ability to conduct California's affairs in the future. With the arrival of the new appointments, Alvarado's main troubles were over, although he still had to contend with minor insurrectionary movements conducted by the Carrillo sympathizers during the early part of 1839. They naturally felt resentful at being left out, and denounced the base ingratitude of the Mexican Government in rewarding rebels while its loyal citizens were not even thanked. The loyalty of the southerners, however, may well be discounted. Thus by the summer of 1839, Alvarado was firmly established as governor and the course of California politics was again running smoothly. In conclusion, it may be said that Castillero had served Don Juan Bautista and California well. He had come almost on his own initiative and with only the weakest of official commissions, yet by dint of his energy, sagacity and tact he had averted a civil war and straightened out a badly tangled political situation. On arriving in Mexico he found the results of his labors undone by the ignorance of the government, and California again plunged in a worse mess By slow, patient work which at times must have been exasperating and must have seemed almost hopeless, he finally succeeded in once more establishing peace in California. In so doing, he stamped himself a an able, patriotic, unselfish statesman and prudent soldier; one who had an intimate knowledge of California politics, as well as a keen appreciation of its potential riches and worth, and its eventual future development. Such a man was well worthy of all the honors that a grateful government might bestow upon him. Having finished his work in bringing peace to California, he was granted Santa Cruz Island a a reward for his labors in 1839. During the early part of 1839, Don Andres was elected a congressman from California, and on May 17, sailed for Mexico aboard the California. There he served capably, later being appointed a paymaster general for California in Mexico. In 1841, he was still writing reports on the condition of the military defenses of California and urging the government to take some action, or the territory would be lost. He remained in Mexico until September, 1845, when he returned to California as commissioner from the government, this time to prepare for the arrival of Mexican troops which the government was planning to send to defend the territory against the Americans. During October and November of that year he made a tour of inspection to the northern frontier including Sonoma and New Helvetia. He also had hopes of negotiating the purchase of Sutter's holdings and fort in order to establish a Mexican outpost there, by means of which American immigration to the Sacramento Valley might be stopped. Castillero distrusted the patriotism of John A. Sutter, so far as his loyalty to Mexico was concerned, and he wanted to remove him from that vital spot in the interior valley because he was certain that Sutter was, giving too much aid to the Americans. Also during 1845 Castillero became interested in and denounced the famous New Almaden quicksilver mine south of San Jose. Early in 1846 he again returned to Mexico to make a report and to speed up the military measures which he knew were so urgently needed, if California was to be saved to Mexico. While he was in Mexico the war with the United States began, and in it he took part. He did not return to California until after the war was over, when he came to attend to his mining interests. In 1849 he became involved in litigations over the mine. These lasted from 1849 to 1861, when he finally gave up his holdings. During all those years he lived mostly in Mexico, making several trips to California. After 1861 his name appears no more in the annals of California, and the details of the remainder of his life are obscure. There is no doubt that he served California with distinction. Would that the territory had had a few more men like him! Then its history might have been vastly different during the Mexican period. [Ed. note: This is an abridged edition of an article which appeared in the September 1935 issue of the California Historical Society Quarterly. INTERPRETIVE PROGRAMS FOR CALERO AND ALMADEN QUICKSILVER COUNTY PARKS Date Program Start Time Park Meeting Location 04/06/96Full Moon Walk8:00 pmAlmaden QuicksilverMcAbee Entrance 04/20/96Wildflowers10:00 amAlmaden QuicksilverMcAbee Entrance 04/28/96Historic/Geologic.3:30 pmAlmaden QuicksilverAlmaden Entrance 05/03/96Full Moon8:00 pmCaleroCalero Office 05/25/96Historic9:30 amAlmaden QuicksilverNew Almaden Entrance 06/01/96Full Moon Walk8:30 pmAlmaden QuicksilverMcAbee Entrance 06/15/96Historical Geologic9:00 amAlmaden QuicksilverNew Almaden Entrance 06/22/96BatsPendingCaleroCalero Parking Lot 07/01/96Full Moon Walk8:30 pmCaleroCalero Office 07/13/96To Be AnnouncedPendingCalero 07/20/96TO Be AnnouncedPendingCalero 08/10/96To Be AnnouncedPendingCalero 08/17/96Historic/Geologic3:00 pmAlmaden QuicksilverNew Almaden Entrance 08/28/96Full Moon Walk8:00 pmAlmaden QuicksilverMcAbee Entrance 09/07/96Geologic Slide Show7:OOpmCaleroCalero Offlce 09/14/96Historic9:30 amAlmaden QuicksilverNew Almaden Entrance 09/27/96Full Moon Walk7:30 pmAlmaden QuicksilverMcAbee Entrance 10/26/96Full Moon Walk7:00 pmAlmaden QuicksilverMcAbee Entrance PROGRAMS ARE OPEN TO THE PUBLIC. FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE CALL 268-3883. This is a not one of Aesop's Fables. You just might see a fox in a tree. A common but elusive local member of the dog family frequently climbs trees. In fact. in some parts of the country, the Gray Fox is known as the Tree-Climbing Fox. I suppose this habit could be helpful in obtaining food such as fruits or insects. but this skill is used mainly for escaping enemies. The slightest lean to a tree or the presence of branches close to the around makes it possible for this little fox to clamber up. Some carry it a bit farther and have been known to have litters of pups in tree holes as much as 30 feet above the ground. These foxes are rather small, about 14 inches high at the shoulder, and they weigh in at about seven to thirteen pounds. They have short legs but a very long name! Urocyon cinereouyenteus is the scientific name. Gray may sound a bit bland. but these diminutive carnivores are actually quite attractive. They are silvery to blue-gray on top, and the belly and legs are yellowish to red. Most commonly they bear their young in well-hidden dens abandoned by other animals or in old culverts or rock piles. Litters average four in number but may be as high as ten. Gray foxes seldom attack poultry or other livestock. They eat both plant and animal matter, and mice and insects probably make up the bulk of their diet. They can be found in much of the United States. usually where there is dense brush or good tree coyer. In most cases. these little foxes seek shelter quickly when pursued. Although they are usually shy, there are times when they seem to be overcome by curiosity, and it is not uncommon to find one sitting in the open watching intently as you go about your gardening or other chores. Of course, curiosity can kill more than cats. Traps catch many of these little fur-bearers, and coyotes and eagles don't hesitate to make a meal of one when the opportunity arises. Even after death, the Gray Fox is easily identified. The skull has ridges on the top that form a large "U." Short for Urocyon, 1 suppose. With a little luck, you might see one of the Quicksilver Park's beautiful Gray Foxes crossing the trail in front of you. Maybe you should look up also-just in case one crosses above you! -Bob Clement |

People |

Castillero, Andres Clement, Bob Knapp, David W. (Sr.) Monahan, Kitty Tonkin Sr., Thomas |

Cataloged by |

Meyer, Bob |