Archive Record

Images

Metadata

Catalog number |

2000.1.101 |

Object Name |

Pamphlet |

Date |

1952 |

Description |

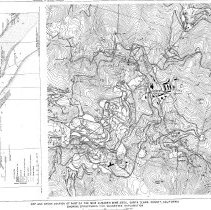

An interesting booklet by the Division of Mines, San Francisco on exploration at the Quicksilver Mine. TITLE: Suggestions for Exploration at New Almaden Quicksilver Mine, California* SUBTITLE: Special Report 17 AUTHOR: Edgar H. Bailey** PUBLISHER: U. S. Geological Survey OUTLINE OF REPORT Abstract 3 Introduction 3 Geology 3 Structures suggested for exploration 4 Illustrations Plate 1.Map and cross-section of part of the New Almaden mine area, Santa Clara County, California, showing structures for suggested exploration 2 - 3 Abstract The geologic investigation of the New Almaden quicksilver mine in Santa Clara County, California, resulted in the location of several areas believed to be favorable for the discovery of new ore bodies. Because ore bodies are found in silica-carbonate rock along the margins of serpentine sills intrusive in Upper Jurassic (?) rocks of the Franciscan group, the search for ore should be guided by a knowledge of the form of the serpentine bodies. Two potential ore structures were discovered by contouring the surface of the principal serpentine mass. The mass is now believed to consist of two main sills joined in the central area; if this is so, other contact areas that may contain ore bodies remain little explored. Introduction The New Almaden Mine, about 10 miles south of San Jose, California, has yielded more than a third of the quicksilver produced in the United States. Between 1941 and 1948 the U. S. Geological Survey made a detailed study of the entire New Almaden district in an effort to determine the relation of the quicksilver ore to the geological structure, and to discover guides that might aid in future exploration arid development work. A comprehensive report on the results of this study is in preparation (1951), but this preliminary report has been prepared to describe some of the more easily tested places that are believed to be favorable for the discovery of new ore bodies. It is not exhaustive, and does not pretend to be an evaluation of the possibilities of the entire district, which also contains other notable quicksilver mines. The price of quicksilver fluctuates with greater rapidity than the price of any other of the useful metals. During World War II it was at a high level, and about 200 quicksilver mines in the United States were in production. After the war period it declined to a value that was probably lower than at any time in the last 100 years, if the changing value of the dollar is taken into account, and as a result all but one of the major domestic mines were shut down. In mid - 1950 the price again rose to a level a little higher than prevailed during World War II. With this price, the quicksilver mining industry has undergone somewhat of a revival. Nevertheless, because of the uncertainty of a high price continuing beyond the period of time necessary to carry out major exploration, development and the construction of a plant to furnace ore on a large scale, much of the current activity is confined to small groups of men seeking small supplies of rich ore to treat in retorts. Unfortunately, such operations yield only a small percentage of the quicksilver needed by our highly industrial nation, and do not result in the development of a self-sustaining domestic quicksilver industry. The search for large new ore bodies in the old quicksilver mines in California in general will require extensive exploration programs, such as can be carried out only by well-financed mining companies. This report calls to attention certain structures that seem to be unusually promising for exploration in the oldest and largest of the California quicksilver mines. Although the abnormally high prices make exploration particularly timely, nevertheless it is quite possible that the proposed exploration might discover ore bodies of sufficient size and grade to be economic even if the price of quicksilver again falls to a low level. The ore bodies mined at New Almaden were among the largest found in any domestic quicksilver mine, and the structures recommended for further exploration are extensive enough to contain ore bodies comparable to those previously mined. The average quicksilver content of the ore furnaced at New Almaden from the time of its discovery until 1900 was about 4 percent; and the relatively small amounts of lower-grade ore taken from underground workings in the early 1900's, although not so accurately recorded, would not reduce this average very much. During World War 11, however, when quicksilver prices were high, it was possible to mine profitably from open cuts ores containing as little as 3 pounds of quicksilver to the ton. The New Almaden mine area has been explored by about 35 miles of underground workings, some of them near the surface and some extending to a depth of about 2,400 feet below the top of Mine Hill, or about 700 feet below sea level. The recent geologic study indicates, however, that there are still a few blocks of unexplored yet easily tested ground that are geologically favorable for the discovery of ore bodies. They remained unexplored during the development of the mine, between 1850 and 1900, largely because the geologic environment of the known ore bodies had not been adequately studied and understood. Geology The oldest rocks of the New Almaden mine area are a part of the heterogeneous Franciscan group of Upper Jurassic (?) age. These rocks are folded, and are intruded by sills of serpentine, the margin of which are altered to a quartz-magnesite rock called silica-carbonate rock. Ore bodies are found in this silica-carbonate rock, close to the original intrusive contacts of the sills. Most of the ore bodies that have been mined extended along the upper sides of sills, close beneath a capping of sheared shale called "alta"; but others, not quite so large but equally rich, extended along the under sides of sills and above alta. Where the contacts are relatively flat the ore bodies are in the crests of domes or arches. Where the contacts are steeper the ore bodies are in places where steep northeast-trending veins of quartz and carbonate are particularly abundant. In both situations the cinnabar replaced the silica-carbonate rock along the vein fractures, but the veins themselves are for the most part virtually barren. As the ore occurs along the altered margins of the serpentine, the search for additional ore should be guided by knowledge of the form of the serpentine bodies. The principal serpentine mass is exposed at the surface in the central part of Mine Hill, and in the past it has been interpreted as having the form of a cedar tree that expanded irregularly downward, being steep but jagged along its south flank and rather smooth ant] gently inclined on the north and east. Most of the ore bodies were found as the result of exploration along the margin of this body and contouring of its surface indicates that at least two structures that might contain ore remain unexplored. These (structures A and B of plate 1) can be probed by drilling near-vertical holes from the surface to depths of 250 to 600 feet. Other potential ore-bearing areas are suggested by a reinterpretation of the shape of the intrusive mass of serpentine. This is now believed to consist chiefly of two main sills that are joined in the central area near the surface of Mine Hill. In this block, where the early workings of the mine were run, the serpentine has the appearance of a single intrusive mass, and, in spite of later development revealing its twofold character, the original concept of a single body was closely followed in the search for ore. The new interpretation, involving two sills, introduces three additional extensive, but little-explored, contact areas that can be expected to contain ore bodies in favorable parts. Structures along two of these (structures C and D of plate 1) appear especially promising and can be reached by drilling holes from the 800-level Day tunnel. To reach the suggested drill stations, however, will require reopening the Day tunnel, which is now caved at the portal and is also caved tight in at least two other places farther in. Structures Suggested for Exploration Structure A. Structure A is an arch in the upper margin of a serpentine sill, at an altitude ranging from 1,000 to 1,150 feet above sea level, under and cast of the camp area (see plate 1). The upper part of the sill has been explored to the south by the Harry workings and to the west and northwest by the Velasco and North Randol workings. A projection of the contact as explored in these workings indicates that between them there is a northwestern arch, with its apex a little east of the main camp area (see plate 1). Similar structures in other parts of the mine have contained ore bodies. That ore-forming solutions have penetrated the area is indicated by the following facts: (1) A small amount of cinnabar occurs in a dolomite vein at the base of the Camp shaft, although most similar veins in the mine are barren. (2) The company surveyors reported finding cinnabar and low grade ore in the northern part of the Harry 800 level. (3) A little cinnabar occurs in chert at the apex of Church Hill, several hundred feet east of the crest of the arch. The structure could most easily be explored by a series of nearly vertical holes, from 250 to 600 feet deep, put down from the surface between the camp and the crest of Church Hill. Structure B. Structure B is also an arch in the upper surface of a serpentine intrusive, at altitudes between 1,100 and 1,350 feet, beneath the saddle northwest of Cemetery Hill (see plate 1). The serpentine surface has been extensively explored to the north and east by the Harry - Cora Blanca workings and to the northwest by the San Francisco workings. Although the margin of the serpentine is not altered to silica-carbonate rock in outcrops between these two groups of workings, all of the nearest underground workings are in silica-carbonate rock, which contains small local ore bodies. The shape of the surface of the serpentine between these two places cannot be accurately predicted from the available data, but, as is shown by the structure contours in plate 1, the intrusive surface is believed to contain a structural nose plunging to the southeast. As similar structures localized ore bodies elsewhere in the mine, this structure seems worth exploring. It can be tested most easily by drilling nearly vertical holes from the surface to depths of 200 to 400 feet. Structure C. Structure C, as shown on plate 1, is a postulated arch northwest of the Santa Rita shaft and from 200 to 600 feet blow the 800-level Day tunnel. Exploration at this place is proposed to test the silica-carbonate rock along the two contacts labeled I and II in plate 1. Contact I is at the bottom of the upper sill, and contact II at the top of the lower. Along each of these contacts some ore has been found at and above the Day tunnel level, but neither has been much explored at lower levels. A part of contact I exposed in a drift, extending eastward from the bottom of the Santa Rita shaft on the 900 level contains silica-carbonate rock but no ore, although the drift was run to search for the downward continuation of ore found on the level above. On the 1,400 level this contact is cut 800 feet west of the section, and near the 1,800 level of the Santa Rita shaft it is cut 450 feet east of the section. Although no silica-carbonate rock was found in either of these last two places, silica-carbonate rock containing ore bodies might be found in the unexplored ground between the 900 and 1,400 levels. If the lower surface of the upper sill is roughly parallel to its upper surface, it is arched between the 1000 and 1200 levels. This structure could easily be explored by drilling holes bearing N. 15(o) 35(o) from the Day tunnel near its intersection with the Santa Rita shaft. As the position of the arch is uncertain, the inclination of exploratory holes should be governed by what is found in the first hole, which should be inclined downward not less than 35ø. Structure D. Structure D is a postulated broad arch in the lower contact of a serpentine sill (contact. III, plate 1) in the central part of the mine, a short distance below the Day tunnel. The contact has not been reached at any point near the line of section, but its position and attitude are inferred from the arch of silica-carbonate rock that is penetrated for more than 600 feet by the Day tunnel. Elsewhere in the New Almaden district silica-carbonate rock is found only along the margins of serpentine sills, and as this silica-carbonate rock is overlain by serpentine it presumably is on the lower side of the serpentine body and is underlain by rocks of the Franciscan group. Exploration on the 900, 1000, and 1,100 levels a little farther to the south revealed Franciscan rocks beneath the contact (see plate 1). The favorable part of the structure involving this contact is the crest of a dome that is inferred to lie east of the old mule barn cutout in the Day tunnel. Indications of the probable existence of ore in this part of the mine are: (1) the Day tunnel follows several northeast trending veins similar to those that generally accompany ore bodies; (2) the highly altered silica-carbonate rock is similar to the rock found along the margins of the stoped-out ore bodies; and (3) when the Day tunnel was driven, cinnabar fines were seen in a spring near the mule barn. A raise that was put up here in search of ore penetrated barren serpentine, but no winze was ever put down to the contact below. The best way to explore this structure is to drill several holes downward and eastward from a point near the mule barn. Any ore that is found can readily be taken out through the Day tunnel. Printed in California State Printing Office *Publication authorized by the Director, U. S. Geological Survey. Manuscript submitted for publication November 1951. **Geologist, U. S. Geological Survey. |

People |

Bailey, Edgar H. |

Cataloged by |

Boudreault, Art |

Collection |

Anonymous/Unknown 1 |